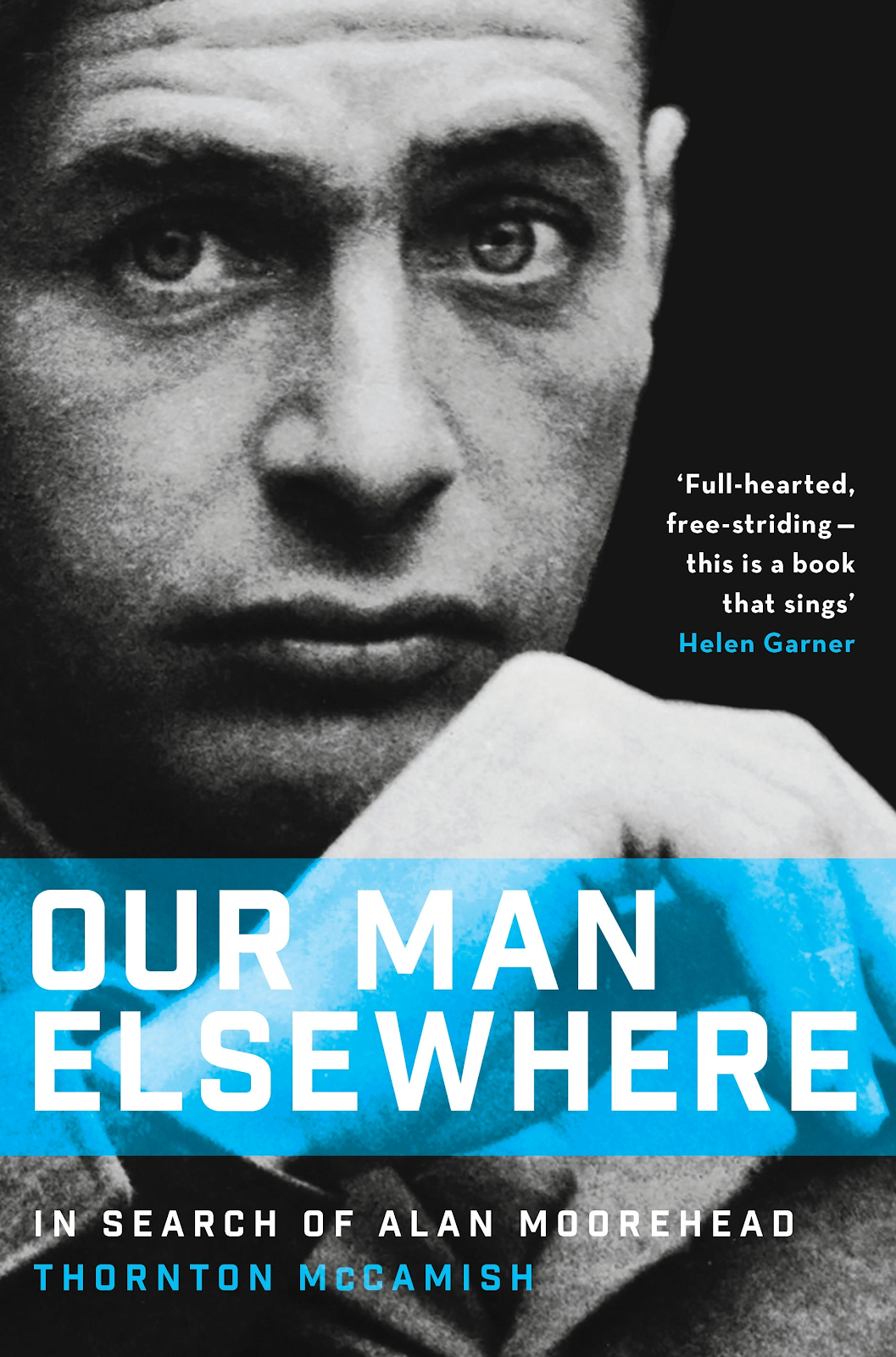

Our man elsewhere : in search of Alan Moorehead by Thornton McCamish

Carlton: Black Books Inc., 2016 ISBN 9781925203110

In the acknowledgements at the end of this book, Thornton McCamish calls his effort a "sort-of biography", which I guess is true, but sells this well-written and entertaining book short. Part detective story, part hagiography, part travel diary, this book about one of Australia's most well-known post-war writers begins by trying to understand a mystery, a mystery that has also intrigued me a little over the years, and a mystery that drove McCamish to great lengths.

Alan Moorehead, at the peak of his powers in the early 1960s, was one of the best-known writers in the English-speaking world, mentioned in the same breath as Hemingway (they were friends, of a sort), and whose latest tome was eagerly awaited by both publishers and readers alike. His version of history as travel, with a bit of himself thrown in, had no equivalent in his own time, and few equals since, and there have been many who have tried to capture the essence of his writing in their own, and failed.

The mystery that McCamish outlines at the beginning of Our man elsewhere is how someone like Moorehead could - half a lifetime after he stopped writing - now incite a response of "Alan who?" if mentioned in conversation, particularly in his home country of Australia (McCamish too is Antipodean).

Like McCamish, I have a deep affection for Moorehead's work. Unlike McCamish, I came to him first through his later books such as The White Nile and Cooper's Creek. McCamish first came across his war writing in the African Trilogy and was instantly swept up by the power of his prose, and the seemingly effortless way he transferred experience to paper. This began a multi-year process of trying to track Moorehead down in archives and on the ground. It seems that at some stages this activity became almost an obsession for McCamish, rather than merely research for a book.

As McCamish gets further into his subject, the reader travels with him across Europe, experiencing his personal reaction to the various revelations he has while walking in the footsteps of his hero. We learn that Moorehead was desperate to leave Australia, and when he did in the mid 30s, his luck landed him on the doorstep of the opening salvos of World War Two.

McCamish, even though he clearly has great respect for his subject, is not averse to describing his less-than-perfect traits, one of which was his pushiness. This characteristic - much unloved by the Englishmen around him - enabled Moorehead to get on the ground in Egypt to witness the Western Desert fighting. When he arrived there he was a working journalist, unknown outside his newspaper, and one of many war correspondents assigned to the theatre. By the time the campaign ended with Allied victory, his byline alone was selling papers, and his successful war books were being put through the presses.

While he was covering the war, he was also having a good time. McCamish conveys the almost University College-like feeling of men being together all for a common purpose, with the danger and discomfort adding to the cameraderie. For Moorehead, it was also like the University education he never received, spending much time drinking and arguing with his contemporary English correspondents, and learning much about the world, literature and history.

At the end of the war, Moorehead was determined to make his mark as a writer, but floundered for the next decade, producing several poor novels (McCamish, ever ready to praise Moorehead's writing, can find little good to say about these efforts - I'm glad he read them so I don't have to), and surviving on articles for magazines such as the New Yorker and others.

He gradually came to realise that his forte as a writer was non-fiction, and over the period from his highly praised book about the Gallipoli campaign to the release of The White Nile he found his true metier - narrative history with an "I was there" feel. His ability to describe places, imagine a place in time and to sketch character, all developed in the crucible of war, were now put to good use, and both The White Nile and The Blue Nile were bestsellers.

As well as these successful books, Moorehead continued to write articles for magazines, and tried (and failed) to get into writing for films. He travelled constantly, but his home base was a house he built in Porto Ercole in Tuscany, and on his brief soujourns there he hosted a constant stream of writers, actors and other members of high society who came and spent time with him. It was a good life.

Writing the book about Gallipoli brought Moorehead back to Australia: when he left in the 30s, he cast aside his home country, to the extent that he even changed his accent. In the early 50s he returned for a short period to write a book aimed at the overseas market (Rum Jungle), which did little to endear him to the Australian literary scene, as it was then. After he finished the Nile books, he was searching around for a new subject, and his friend Sidney Nolan (Moorehead was on friendly terms with many artists) suggested the Burke and Wills story as suitable. The result was not only Cooper's Creek (still the best treatment of the Burke and Wills expedition), but a realisation by Moorhead that his home country did have a lot to offer a writer. True, it had no long human history in the European sense (which is why he left in the first place) but it was a country that was still in the process of creating its (white) mythic stories, and those stories contained much that was of interest to a writer.

This homecoming for Moorehead was therefore a physical and a psychic one, and he was finding his endless wanderlust was passing (his other desires however were another story; an inveterate womaniser, McCamish deals with Moorehead's numerous affairs and flings with honesty and tact).

Then tragedy struck - the stroke he suffered at the end of 1966 stopped his writing for the rest of his life, and meant that his final 15 years were one of limited horizons: he couldn't really communicate much verbally, was essentially unable to read and could not write (he could however, paint, with his left hand). The fact that he published two further books is down to his wife Lucy, who managed to gather together and edit material that emerged as Darwin and the Beagle and A late education. Lucy comes through in this book as an equal partner in the Moorehead "business" - since the war she had been essential in his output - typing, editing, dealing with publishers and making sure business was finished, as Alan was travelling and writing.

All of this is related by McCamish in an easy-to-read way; interspersing his own story of tracking down his hero and revisiting places Moorehead stayed or visited and comparing the now to the then. Once into the book the reader realises that what McCamish is doing is writing a Moorehead book: a narrative history with a present-day "I" at the centre. It is a touching tribute to Moorehead, and a successful one too - many books of this type fail because the "I" becomes too intrusive, but invariably in Our man elsewhere McCamish's appearances add to, rather than detract from, the story.

The quibbles I had with the book were few - a couple of editorial mistakes (Frank Clune, not Cluny, and I couldn't find the article in Horizon magazine that was mentioned) and a very occasional slip in McCamish's evocation of the past (in Melbourne in the early 60s they would be drinking Claret and listening to the wireless, not Fruity Lexia with a radio). McCamish has a wonderful way of expressing what it's like to research thoroughly for a book; I loved how he hated to see the name Morshead in the index of books because it meant there was no mention of his pet subject (resonating with me because I'm often looking for Morshead and am annoyed at Moorehead appearing!).

McCamish also had problems with Moorehead's view on topics such as native Africans and Australian Aboriginals, wondering why Moorehead wasn't more progressive, but he was certainly a man of his time, and a man of Empire toboot, so it would seem to me that his views were of a piece with that. Where Moorehead was ahead of his time was in his views on conservation, with No room in the Ark and The fatal impact years ahead of their time in their description of man's impact on other life. It would have been interesting to see how Moorehead's writing developed in that area if he hadn't had his stroke.

As with all good biographies of writers, Our man elsewhere reminded me of what I should revisit, told me things I didn't know (i..e. that he didn't die until 1983!), and has driven me to some of Moorehead's work that I hadn't read. By the end of the book, as McCamish revisits the Moorehead archive at the National Library of Australia for one last time, he himself seems to reach the end of his obsession, and can comfortably close the cover on what is an interesting biography of an interesting man.

Highly recommended.

Cheers for now, from

A View Over the Bell

No comments:

Post a Comment