That Deadman Dance by Kim Scott

Sydney: Picador, 2011 (first published 2010) ISBN 9780330404235

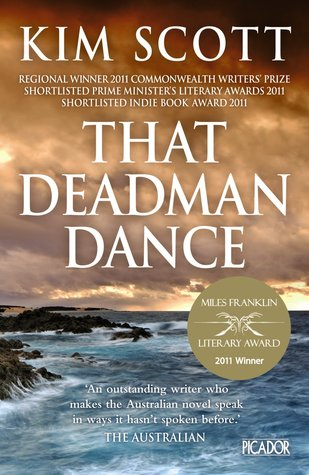

The blurb on the front cover of this paperback edition, (from a review in The Australian newspaper) gushes "An outstanding writer who makes the Australian novel speak in ways it hasn't spoken before." Alongside this quote is information telling the reader that not only was this book shortlisted for the Prime Minister's Literary Awards and shortlisted for the Indie Book Award, it was the regional winner of the 2011 Commonwealth Writers' Prize and won the 2011 Miles Franklin Award.

So the question needs to be asked - does it live up to the hype? Well....it's a much better book than some other Miles Franklin winners that I have read, but I really don't think the book "... makes the Australian novel speak in ways it hasn't spoken before." In fact in some ways I think That Deadman Dance travels a well-worn path in Australian literature, albeit with a slightly different focus.

After all that preamble, I will state up front that this is a good novel. It's well written, well paced, and evocative. The story it tells is interesting and how it is told adds to that interest. I found the ending unsatisfactory and a bit formulaic, but others may not see it that way.

Simply put That Deadman Dance is a story of the early settlement by white men of the southern coast of Western Australia (Kim Scott is an indigenous man of that area). The story is told mostly through the lens of "Bobby" Wabalanginy, who begins the story as a precocious orphan taken under the wing of the military surgeon of the initial British party to land in Bobby's tribal area, setting up the settlement of King George Town. The surgeon, Dr. Cross, is careful to treat the Aboriginal people well, fully understanding that without them and their assistance the white men cannot hope to survive. The passage of time that occurs during this novel shows the unravelling of this initial partnership, where give-and-take between the two cultures changes to the whites taking from the blacks without any recompense.

Scott's tracing of Bobby's life, from being an indispensable bridge between black and white as well as an important worker for the settlement in their efforts to expand pastoralism and whaling, to him ending up a tourist attraction telling his stories after leading what was effectively a rebellion against the white takeover of his land, contains pathos and humour.

Geordie Chaine, who befriends Bobby after the death of Dr. Cross, is the white man who builds King George Town and the surrounding area up from "nothing", to the thriving settlement it has become by the end of the book, is a sympathetically written character. The reader knows that he thinks the blacks are a lower order of people than white, but he is happy for them to live alongside his world as long as they are "useful". He is genuinely sad when Bobby leads his people in stealing food, but completely fails to understand, unlike Cross, that he had stolen everything from Bobby's people when he fenced the land for his stock, killed all the wildlife to feed the whalers who were overfishing the seas. When imprisoned for stealing stock and provisions, Bobby explains how he must feed his people, and when Dr. Cross and the white men came Bobby's people shared the land, and he is merely doing the same now with the white man's stock and stores, given the land has been stripped bare of traditional food by Chaine and his compatriots.

Scott suggests in the novel that it could have been different. Jak Tar, a deserting whaler, partners with Binyan, a local Aboriginal woman, in a loving relationship. While their love transcends their cultural differences, it is not only the white people who spurn the two of them: the elders of the tribe do as well. It seems that mutual understanding can only reach so far.

This area of Western Australia, as Scott notes in an afterword, is sometimes known by historians as the "Friendly Frontier", as there was very little fighting between black and white. As Scott makes clear though, even without such skirmishes many indigenous people died from disease (as did whites), and the resulting dispossession was no different to other areas.

Scott is skilful in his characterizations. Bobby is a wonderfully drawn character, interested in everything and everybody, and everybody interested in him and what he does. He is a joyful and positive presence even when things are going badly. Dr. Cross and his good friend Wunyeran represent first contact in a positive light, while Menak and Chaine well represent the respective feelings of both sides as settlement became more permanent. Chaine's daughter Christine, who grows up with Bobby, is also well-drawn, in her confusion of her place in the world, and Bobby's. Each of these characters along with the ex-soldier Killam and the ex-convict Skelly represent a part of a wider narrative, but none are cardboard cut-outs - Scott writes well.

So, has this novel broken new ground, as the blurb on the cover might suggest? No, not really. But, it is certainly a good story well written, and one that will stay with me for some time. Recommended.

No comments:

Post a Comment